Taking advantage of a growing embrace of the digital age by financial scientists in the 1960s, a youthful Eugene Fama decided to explore in his PhD thesis paper better ways to measure and explain the random nature of stock market prices.

Taking advantage of a growing embrace of the digital age by financial scientists in the 1960s, a youthful Eugene Fama decided to explore in his PhD thesis paper better ways to measure and explain the random nature of stock market prices.

At the time a grad student at the University of Chicago, he later credited long walks with renowned applied mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot for helping to spark his interest in such a topic. Known for his research into financial securities pricing, Mandelbrot was part of an emerging academic consensus arguing that current models fell short in quantifying stock fluctuations.

Also bolstering Fama's sense that empirical studies at the time needed more statistical refinement was Merton Miller, his thesis supervisor at the Booth School of Business.

Miller, who would later win a Nobel Prize in 1990 along with Harry Markowitz and William Sharpe, reportedly so liked Fama's ideas about ways to advance research into securities markets that he rejected four other suggestions made by his grad student at the time. As recounted in Colin Read's classic book "The Efficient Market Hypothesists" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013):

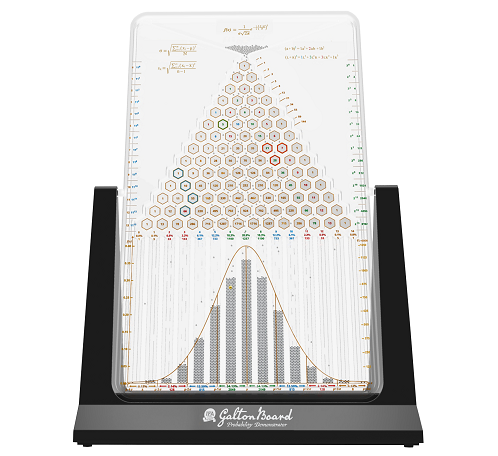

"(Fama) proposed to explore for himself whether Mandelbrot's belief that price distributions display fatter tails, or more extreme price departures, than predicted by the normal distributution was indeed well founded. Researchers had observed for decades that these price distributions seemed to violate the assumed Gaussian distribution that results when the unexplained residuals of prices follow a random walk. Fama began to explore whether these residuals are also serially correlated rather than random and uncorrelated over time."

Building on the ideas of other leading scholars — such as Louis Bachelier, Alfred Cowles and Paul Samuelson, among others — Fama set out to develop a comprehensive theory. In the process, he wound up developing the Efficient Market Hypothesis, a key research finding that helped to advance portfolio management from art to science.

How influential was Fama's research? In their book "The Fama Portfolio" chronicalling developments in the financial sciences, professors John Cochrane and Tobias Moskowitz include a scholarly paper by G. William Schwert and Rene Stulz analyzing Fama's impact for investors. In part, it reads:

"Gene Fama has been the most prominent empiricist in finance for 50 years. He is the founder of empirical research in modern finance."

They add: "A scholar can impact the world at large as well as his academic discipline. There are no easy quantitative measures of his impact. But we know Gene's impact is enormous. 'Efficient Markets' is a household name throughout the world. The efficient markets view inspired countless laws, regulations, accounting practices and policies ... It affects how investors make their investment decisions and evaluate their performance."

Interestingly, Fama's sense of purpose in quantifying stock price movements and random distributions traces its roots to when he worked for a stock market newsletter firm while attending undergraduate school in Boston. One of his duties was to find "buy and sell signals" based on certain market trends. He experienced firsthand the difficulty in predicting future market trends. As recounted years later, Fama began to wonder — just as Cowles and others had before him — why it was so difficult to translate what appeared to be neatly defined past trends into "sure" methods of making money in the stock market.

Such ponderings influenced him enough to spark interest in attending the University of Chicago. His longer-term goal was to earn a doctorate and become a professor teaching classes on the works of Markowitz. It seems that despite the innovative character of Markowitz's writings, his work had largely not attracted a lot of attention in academia. In fact, Fama sought to heighten studies of the work of Markowitz and others through the storied University of Chicago's graduate finance program.

Fama not only achieved great success doing just that, but he also became one of the most prolific and often-cited academic researchers of financial securities. In 2013, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

It's probably worth noting that Fama's work attracted substantial attention from the outset. In January 1965, for example, the prestigious Journal of Business published Fama's entire 70-page PhD thesis, "The Behavior of Stock Market Prices." (See image to the right.) It was summarized nine months later by another respected academic publication, the Financial Analysts Journal, in a piece titled "Random Walks in Stock Market Prices."

Essentially, Fama sought to challenge the widely held belief that major brokerage firms had a tremendous advantage in picking stocks. The argument was that such huge broker-dealer networks held vast resources to tap into information on everything from individual securities data and portfolio returns to corporate ledgers and other accounting-related (i.e., company specific) information. Supposedly, brokers also were thought to hold the upper-hand since they were able to take such data and talk to corporate managers, consulting economists and politicians.

As a result, active securities selection in Fama's early days was largely presented by brokers as almost a fait accompli — i.e., a securities analyst in the early 1960s should be able to consistently outperform a randomly selected portfolio of securities of the same general risk.

Since in any given situation, the analyst has a 50% chance of outperforming the random selection — even if the researcher's skills are nonexistent — Fama's conclusion was that active managers do not consistently outperform a market.

In 1970, Fama published the Efficient Market Theory (EMT) in "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work," in which he concluded equity markets consistently incorporate all available information into their prices, and trends in capital markets cannot be identified in advance. Subsequently, Fama and Kenneth French — his frequent research partner — wrote a paper in 1992 that expanded on the Nobel Prize-winning research of Markowtiz and Sharpe that developed the Modern Portfolio Theory.

In their research piece, "The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns," Fama and French determined that exposure to market, size and value risk factors could explain as much as 96% of historical returns in diversified stock portfolios.

The bottom line: The EMT explains the workings of free and efficient financial markets. All known and available information is already reflected in current stock prices. The price of a stock agreed on by a buyer and a seller is the best estimate, good or bad, of the investment value of that stock. Stock prices will almost instantaneously change as new unpredictable information about them appears in the market. All of these factors make it almost impossible to capture returns in excess of market returns, without taking greater than market levels of risk.

It is relatively rare to find and profit from a mismatch between a stock's price and its value, or to identify an undervalued or overvalued stock through fundamental analysis of stocks. This creates efficient financial markets where most stock prices accurately reflect their true underlying investment values. Even when stock prices do not reflect their values, attempts to establish more accurate values usually cost more than the profit to be made from successful efforts to do so.

Such empirical findings threaten the view that there might be something pinning down the average price of an asset. Deviations of an asset price from this value follow a random walk. This annoyed those who claim that they could anticipate speculative trends in asset prices. The research by Fama showed that active managers on the whole couldn't be relied upon to beat a respective market index because any available information is already incorporated in the price.

This has created much argument in the active management industry. But an educated investor can be a real thorn to any aspiring stock jockey. One of the earliest instances in which notable members of the media started to shine a light on such advances in financial science came at the 1968 Institutional Investor conference. In this event, an irate money manager insisted that what he and others did for investors had to be worth more than just throwing darts at the Wall Street Journal. The "dart board portfolio" soon became a new benchmark for active investors, appearing in newspapers and magazines.

It became such a hot topic of discussion among investors that by 1992 the ABC News show "20/20" decided to run a segment entitled, "Who Needs the Experts?" In this piece, a giant wall-sized version of the Wall Street Journal was made into a dartboard. Reporter John Stossel threw several darts as he described the firms he randomly hit. The results of that portfolio were compared to those of the major Wall Street Firm experts.

Probably not surprising to students of Eugene Fama, the darts beat 90% of the experts. When ABC requested interviews with several of these expert firms, not one of them would speak or comment on their humiliating inability to beat the darts.

The work of Fama was cited by Burton Malkiel in his book, "A Random Walk Down Wall Street." First published in 1973, it helped to popularize the Efficient Market Theory (or, Hypothesis, as it's sometimes called). But it's worth noting the random nature of stock market prices wasn't just an idea that appeared out of nowhere. In fact, statistical studies pointing to a lack of discernible and finite patterns in securities pricing date back as early to Bachelier's work in 1900 — as well as later studies by Holbrook Working (1934), Cowles (1933, 1937), Clive Granger and Oskar Morgenstern (1963), and Samuelson (1965). Fama took the theory to new heights with enough rigorous statistical analysis to shake up Wall Street.

In our view, the biggest problem in getting this information out to the public was that nobody had figured out a way to convert academic research into a practical product. Unfortunately, most fund managers in the past have profited from the active trading of investment portfolios. Fortunately, today there are index funds incorporating virtually all the research described in this timeline.

Along these lines, Fama joined Dimensional Fund Advisors in 1981 as a founding director. The funds provider was started by one of his former students, David Booth. (For more information on Fama's curriculum vitae and links to his research pieces, please see IFA's article "Eugene Fama: One of a Kind.")

This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product or service. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Hypothetical data is provided for illustrative purposes only, it does not represent actual performance of any client portfolio or account and it should not be interpreted as an indication of such past or future performance.