Human beings are not cut out to be a good investors. Instead of basing investment decisions on logic, data and evidence, people are much more likely to act on instinct, impulse and emotion. That's why, generally speaking, a good advisor is well worth paying for. As Mark Hebner puts it in Step 12 of his book, Index Funds: The 12-Step Program for Active Investors, "an investor may want to consider the fees paid to an advisor as a casualty insurance premium, insuring investors against their own mistakes and lack of knowledge."

That said, choosing the right advisor to work with is crucially important. If you make the wrong choice, you may not achieve your financial goals; indeed, your advisor could even do more harm than good.

When choosing an advisor to work with, here are some questions you might want to ask them: What is your investment philosophy? Do you provide services that aren't directly related to investing, such as tax planning or estate planning? Are you a genuine fiduciary?

Here is another question you could put to them: Can you explain standard deviation and what a t-stat is? Now this might sound flippant, but it's not. If they can't do it, you probably shouldn't hire them. Let me explain.

A fundamental requirement for an advisor

An understanding of statistics is a fundamental requirement for anyone providing investment advice. It enables them to analyze data effectively, make informed decisions, and manage investment risks. Statistical tools help advisors to assess the probability of investment outcomes, and construct diversified portfolios that align with clients' financial goals.

No matter how persuasive an advisor is in recommending a particular strategy, without a grasp of statistics it can easily go awry.

Note, it's not enough for an advisor to have a mathematical brain. It helps, of course, but pure mathematics is an abstract science. Statistics, on the other hand, is a branch of applied science that focuses on the collection, sorting, and representation of data. An advisor has to understand all of those things to do their job properly.

Standard deviation and t-stats

So why are standard deviation and t-stats particularly important? Well, standard deviation measures the dispersion of returns around the average return of an investment. It helps us to gauge the risk associated with that investment. To quote Mark Hebner, it "provides a statistical measure of historical volatility, sets forth a distribution of the ranges of probable future outcomes, and establishes a framework of risk and return trade-offs."

A t-stat, or t-statistic, is a measure of statistical significance. It shows us how much or little weight to attach to a specific collection of data. This is vital for an advisor because data is really all they have to go on when making investment decisions, and they absolutely need to know the significance of the data in question.

Short-term movements in the financial markets are essentially random; they tell us little or nothing about future returns. Although there is value in looking at returns over very long periods of time, history doesn't repeat itself exactly; what happened in the past is only one of many possible future outcomes. From an empirical standpoint, therefore, it's helpful to think of numerous parallel universes of different outcomes drawn from the same underlying capital market process.

As Brad Steiman from Dimensional Fund Advisors explained in a recent IFA article, "an analysis of historical data should aim to identify risk-and-return relationships without placing too much weight on a period-specific result. Consequently, empirical research should always incorporate statistical tests designed to calculate the likelihood that the results occurred by chance.

"Investors who understand statistical significance will have a much better frame of reference for interpreting results that help us hone in on our best guess." 1

One of the reasons why most investors, including professional ones, achieve suboptimal returns is that they are far too focussed on time periods that are far too short. They assume, for example, that an active fund manager who has outperformed, say, for three or five years, will continue outperfoming in the future. But, at any one time, there are so many funds to choose from that there will always be funds that have outperformed in the recent past, and the proportion of funds that do so is entirely consistent with random chance.

How long does it take to prove a manager is skilled?

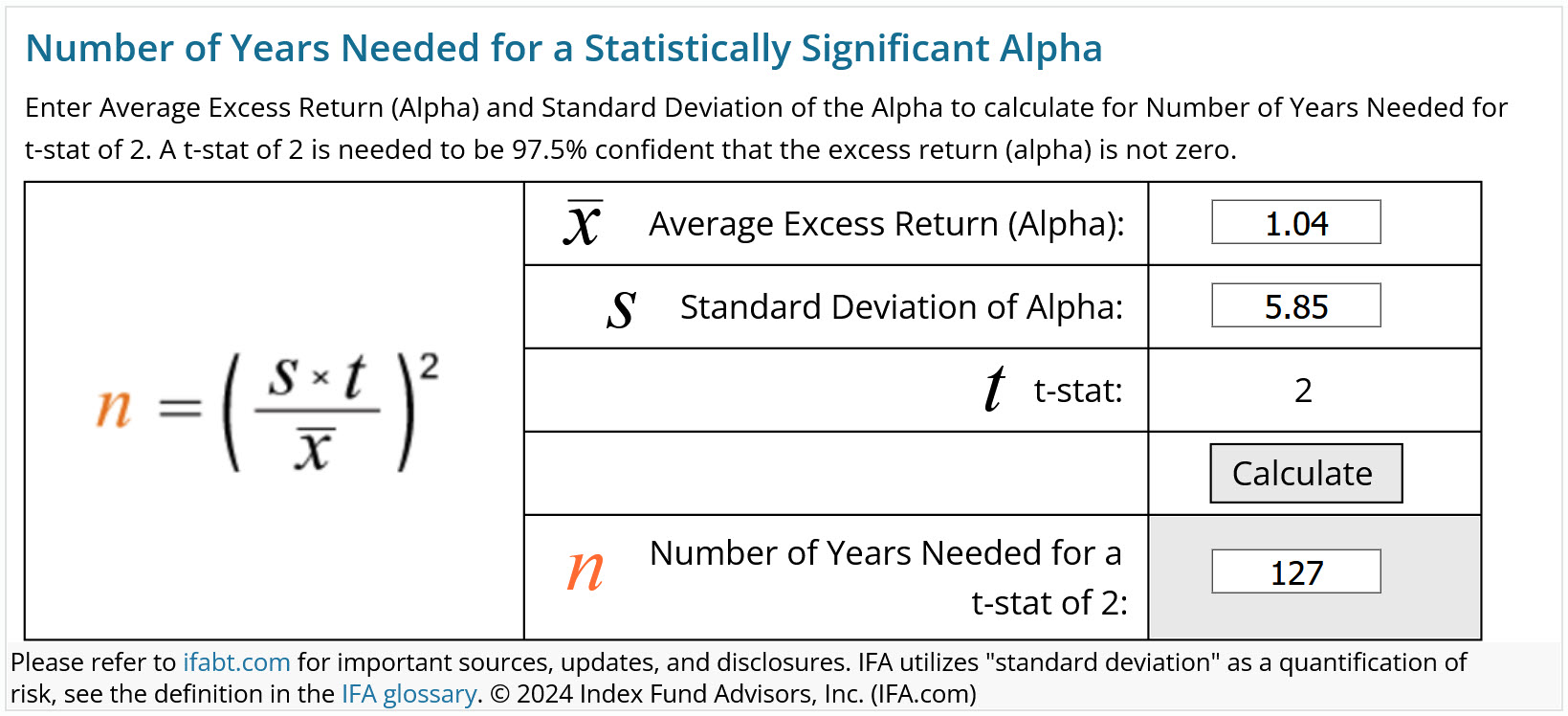

I'm not going to explain here how t-stats are calculated — Steiman's article is an excellent primer if you're interested — but it requires a t-stat of 2 to be 97.5% certain that an active manager is genuinely skillful. So how long a track record is required for a manager to obtain a t-stat of 2? Well, my colleagues at IFA have run the numbers, and the results are contained in the chart below. Based on the average alpha (1.04%) and the standard deviation of that alpha (5.85%) among managers with 20 years (n=20) of returns data, the answer is (wait for it) 127 years. That's right, to be 97.5% certain today that a particular manager with that alpha and standard deviation of alpha has genuine skill, they would need a personal track record dating back to 1897!

Sadly, most financial commentators lack this kind of understanding. But it isn't just journalists who struggle with statistics. In my experience, many advisors do as well. If they properly understood it, why do so many of them still invest their clients' money in actively managed funds? Why do they continue to recommend managers on the strength of just a few years of good performance?

The fund management industry likes to blind investors — and advisors — with statistics which are often highly misleading. As the old saying goes, there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics. Having a high degree of statistical sophistication helps us to sort reliable from unreliable data, and useful information from lies.

Statistical knowhow also enables advisors to identify the right types of risk to take and to choose funds that maximize the expected return for the level of risk that a particular client has the capacity for.

Charles Ellis explained it like this in his 1985 book Investment Policy: "The average long-term experience in investing is never surprising, but the short-term experience is always surprising. We now know to focus not on rate of return, but on the informed management of risk."

The informed management of risk is the guiding principle behind our investment process here at IFA.

Lessons for investors

What, then, are the key takeaways for investors?

First, beware that periods you may have previously thought of as "long term" are mostly noise.

Secondly, never extrapolate the recent past or draw conclusions from short periods.

Thirdly, look for a financial advisor who can help you to focus on your long-term goals and remind you of what the long-term evidence tells us whenever you feel tempted to change course.

And finally, choose an advisor who really understands statistics. If they look at you blankly when you mention t-stats, politely thank them for their time and look elsewhere.

Robin Powell is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

1) Quotes and pictures are utilized for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as an endorsement, recommendation, or guarantee of any particular financial product or service provided by Index Fund Advisors, Inc. or its advisors.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.