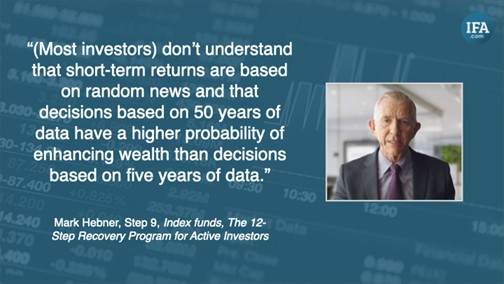

One of the most important rules of successful investing is to focus on the long term. Arguably, it's also the rule that investors ignore most often. As Mark Hebner writes in Step 9 of his book Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors: "Most investors don't make decisions based on long-term history… They generally look at the most recent one-, three- ,five-, and sometimes ten-year returns and assume that recent past performance will be an indicator of future returns."

It's not just ordinary investors who make this mistake. Institutional investors, who are supposed to be more sophisticated than the rest of us, are far too fixated on short-term data. In fact, financial professionals, who should know better than most that it pays to think long-term, are perhaps more focused on the short term than anyone. Why? Because they're financially incentivized to produce results over short periods of time.

The problem is that, because the financial markets are generally very efficient, short-term investment outcomes are essentially driven by random news. Yes, long-term historical data can be very useful, but most investors need to revise their view on what long-term actually means. The standard timeframes for evaluating past performance are far too short to allow us to draw anything like firm conclusions about what the future prospects are for a particular fund, asset class or investment strategy.

The fired beat the hired

A classic example of this unhealthy emphasis on short-run performance is the way that investors hire and fire fund managers on the basis of only a few years of data. A key academic paper referred to in Hebner's book is The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors by Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal, which was published in 2008.

Goyal and Wahal examined the processes by which plan sponsors, such as pension funds, chose funds to invest in. What they found was that funds were selected largely on the strength of their past performance — especially their recent past performance.

Interestingly, instead of adding value, the hiring and firing of fund managers actually subtracted it. On average, plan sponsors did not experience improved performance after changing investment managers. After the changes were made, despite the detailed analysis that went into selecting them, the new managers typically delivered worse performance than the managers who were fired!

A 2013 paper, Picking winners? Investment consultants' recommendations of fund managers, by Tim Jenkinson, Howard Jones, and Jose Vicente Martinez, produced similar conclusions. Investment managers recommended to plan sponsors by investment consultants, the authors found, did not, on average, outperform managers they didn't recommend.

"It is hard to assume that plan sponsors know whether investment consultants add value or not," they concluded. "Consultants themselves are shy of disclosing the sort of information which would allow plan sponsors, or any outsider, to measure their own performance."

How long a track record is needed?

So how long does it take for a fund manager to prove that they are genuinely skillful and have a reasonable chance of outperforming in the future? Paul Kaplan and Maciej Kowara addressed this question in a paper entitled Are Relative Performance Measures Useless?, published in 2019.

The biggest problem we have when evaluating active fund performance, Kaplan and Kowara explained, is that a fund that ultimately outperforms its benchmark may go through a long period of underperforming it.

"For example," they wrote, "a fund that ultimately outperforms over a 15-year period could have gone through an eight-year sub-period in which it underperformed. At the end of such a bad stretch, investors who evaluated the fund solely based on eight years of performance would have missed out on the subsequent outperformance.

"The converse is also true: A fund that ultimately underperforms its benchmark over a 15-year period could very well have gone through an eight-year sub-period of outperformance, enticing performance-chasing investors to buy the fund, only to be disappointed by subsequent underperformance."

So the question that Kaplan and Kowara set out to answer was this: Assuming a manager is skilled and has a good chance of beating the benchmark over a set timeframe, over how long a stretch can that manager be reasonably expected to underperform within that period?

The authors used a Monte Carlo model to produce probability distributions for managers who have (1) positive skill, (2) no skill, and (3) negative skill versus their benchmarks. They then compared the results of the Monte Carlo simulation with the empirical analysis of actively managed global equity funds.

Kaplan and Kowara set the percentage of managers with skill at 25 percent. It's worth noting that this figure is more than ten times higher than the two percent or so of skillful managers Eugene Fama and Ken French found in their 2010 study, Luck versus Skill in the Cross-Section of Mutual Fund Returns.

Yet even with this generous assumption, the researchers found that a fund manager who has the skill to outperform the benchmark over a 15-year period with a 75 percent probability could easily end up with a run of nine-and-a-half years of underperformance before ultimately outperforming the benchmark over the full 15 years.

Active investors face two separate challenges

In other words, the analysis showed, active investors had two hurdles to overcome in order to beat the market. "On average," the authors concluded, "to hold outperforming funds over this 15-year period (you) needed not only to pick the right funds but also to have the patience to endure nine- to 11-year periods of underperformance at some point within that period."

In practice, spotting an outperformer in advance is extremely difficult, and so is keeping faith in your chosen fund after several years of poor performance. To manage both is a very rare achievement.

In conclusion, Kaplan and Kowara wrote, their findings "clearly undermine" long-standing methods for monitoring and evaluating investment managers. "Ten years of outperformance is regarded as conclusive evidence that the investment manager possesses skill,' they wrote. "(But) that is not so. Often these seemingly meaningful findings are nothing more than random noise."

Remember, this particular study assumed that 25 percent of fund managers possess positive skill. If Fama and French are correct in saying that the true figure is really around two percent, the length of time required for a manager to prove they aren't just lucky has to be far greater than ten or 15 years.

What if we apply t-statistics?

Our own view at Index Fund Advisors is that you need to apply t-stats to evaluate past performance by active managers properly. A t-stat, or t-statistic, is a measure of statistical significance.

Without going into detail about how t-stats are calculated — this article by Brad Steiman from Dimensional Fund Advisors is an excellent primer if you're interested — it requires a t-stat of 2 to be 97.5% certain that an active manager is genuinely skillful.

So how long a track record is required for a manager to obtain a t-stat of 2? Well, we've run the numbers on active managers with a record of at least 20 years, and the answer is a rather staggering 127 years.

In other words, to be 97.5% certain today that a particular manager has genuine skill, they would need a personal track record dating back to 1897 — the year that William McKinley became President and Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee!

Long-term? Think 50 years, not ten

What all these studies show is that, when it comes to investing, we need to redefine what we mean by long-term. Ten years is very definitely not long-term. In Mark Hebner's view, you shouldn't be basing decisions on anything less than 30 — and preferably 50 — years of data.

Hebner writes: "Statisticians require data from periods of at least 30 years to minimize the sampling error of short-term data and to provide a more reliable estimate of expected returns and risk. Very few managers are able to provide 30 years of data to their clients."

So next time you read about a fund that's been "shooting the lights out" and is worth investing in, ask the question, Was it around in 1994 or, better still, 1974? And, if it was, has it genuinely beaten its benchmark since inception? The overwhelming likelihood is that it hasn't.

HOW CAN WE HELP YOU?

Do you have any questions about this subject, or any other issue related to investing? If you do, we would love to address them in future content.

Simply email your question to [email protected] with your name and where you live and we'll do our best to answer it.

Robin Powell is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Quotes and images included are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as endorsements, recommendations, or guarantees of any particular financial product, service, or advisor. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.