Americans and Much of the World Are Paying for Decades of Excess

"Persuaded as the Secretary is, that the proper funding of the present debt, will render it a national blessing…he is so far from acceding to the position, in the latitude in which it is sometimes laid down, that "public debts are public benefits," a position inviting to prodigality, and liable to dangerous abuse—that he ardently wishes to see it incorporated, as a fundamental maxim, in the system of public credit of the United States, that the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment. This he regards as the true secret for rendering public credit immortal."

—ALEXANDER HAMILTON, First Report on the Public Credit (January 9, 1790)

A New Era of Financial History

My recently published book, Investing in U.S. Financial History: Understanding the Past to Forecast the Future, separates the roughly 230-year financial history of the United States into six eras. The longest lasted roughly 75 years; the shortest lasted 15 years; and the average was 39 years. The reason for the variance is because historical inflection points are driven by fundamental shifts in the economy and financial system, rather than the passage of a specific number of years.

The final era of the book began in 1982 with the end of the Great Inflation and rise of Silicon Valley, and it ended in March 2023 amid the depths of post-COVID-19 inflation. Now, it appears the U.S. is entering a seventh era. The title remains hidden by the inherent uncertainty of future events, but I suspect the most powerful theme will be the nation's reckoning with chronic, unsustainable spending habits that began soon after World War II ended in the summer of 1945. To be clear, the consequences of decades of unsustainable spending were hardly a secret in the 2010s, but the tremendous costs of the COVID-19 pandemic pulled the day of reckoning forward by several years.

The bad news is that rebuilding the wealth of the American Empire will take a long time and will be painful. There will be extreme winners, extreme losers, and everything in between. The good news is that the 234-year financial track record of the United States strongly suggests that the American people will solve these problems just like their ancestors solved seemingly insurmountable problems in their time. The coming waves of struggle, suffering, healing, and growth will form another set of lesions on the battle-scarred body of this nation. But if history offers a vision of the future—and it usually does—the American people will endure and emerge stronger for having passed yet another grueling test of their resilience.

The Character of the Next Era

The seventh era of U.S. financial history begins with the second term of President Donald J. Trump. Like many presidents who come to power during transitions from one era to the next, President Trump is revered by supporters and despised by detractors. This newsletter does not address the substance of these diametrically opposed views, nor does it take a position on the many contentious social issues. Having taken an oath of political neutrality (see the note below), I only comment on the underlying economic currents that help explain the current state of affairs.

The newsletter opens by identifying several parallels between the Great Inflation of 1965-1982 and the first half of the 2020s. Specifically, it explains how massive, pandemic-related fiscal stimulus, combined with a Federal Reserve that was unwilling to abandon a long-standing dovish bias, allowed high levels of inflation to persist for nearly four years. It then addresses the issue of chronic, unsustainable fiscal deficits and the unwieldy debt burden that they have created. It concludes by explaining important consequences for the rest of the world now that the U.S. is turning inward in a way that world leaders have not witnessed for nearly a century. Rebuilding the wealth of the nation has clearly taken center stage. This does not mean that the U.S. will completely abandon its engagement abroad, but it does mean that allies, trading partners, and enemies would be wise to assume that they are dealing with an empire that will place its own interests above all others for quite some time. The Trump Administration's use of tariffs, freezing of foreign aid, and plans to withdraw military support are manifestations of this philosophical shift.

A Note on Political Neutrality

Some readers may feel this newsletter is too conservative, while others may believe it is too liberal. I assure you my aspiration is only to be factual. This is because relatively early in the process of writing Investing in U.S. Financial History, I concluded that political neutrality is essential to maintaining credibility. I reached this conclusion after watching many historians and economists dilute the impact of their work by allowing personal political beliefs to alter the presentation of what should be sterile facts.

Maintaining political neutrality is difficult, and it does not mean I will refuse to comment on the potential impact of financially relevant political decisions. It just means that when I do offer commentary, I will do my best to take the perspective of an observer rather than supporter or dissenter. Regardless of what happens in this world—no matter how extreme—I will strive to maintain this standard. In short, my goal is to live in the past, observe the present, and combine insights from both to help shed light on the future.

Echoes of the Great Inflation

"People have come to feel in increasing numbers that much of the government spending sanctioned by their compassion and altruism was falling short of its objectives: that the quality of public schools was deteriorating, that crime and violence were increasing, that welfare cheating was still widespread, that collecting unemployment insurance was becoming a way of life for far too many—in short, that the relentless increases of government spending were not producing the social benefits expected from them and yet were adding to the taxes of hard-working people and to the already high prices they had to pay at the grocery store and everywhere else. In my judgement, such feelings of resentment and frustration are largely responsible for the conservative political trend that has developed of late in the United States."

—ARTHUR BURNS, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (September 30, 1979)

When comparing past eras to the present, it is impossible to find a perfect match. This is because, as Mark Twain reportedly said, history tends to rhyme rather than repeat. But if a comparable must be chosen, the Great Inflation of 1965-1982 seems like the best choice. The opening quote from Arthur Burns, who chaired the Federal Reserve from 1970 to 1978, describes several underlying frustrations that probably feel familiar today—and much like today, these frustrations were amplified by persistently high levels of inflation.

Thus far, the post-COVID-19 inflation is less severe than the Great Inflation, but the two events have much in common. Most importantly, at the heart of both were excessive federal government spending and overly dovish monetary policies. Another similarity is the tendency of today's politicians to place far too much blame on pandemic-related, supply chain shocks. This is reminiscent of the excuses used by politicians in the 1970s when they placed inordinate blame on oil embargoes. It is true that both inflationary episodes were amplified by supply shocks, but they were not the most important factors. Another similarity is the clash between conservative and liberal values on a variety of social issues. Although the various issues subject to debate are different today, the intensity of the conflict is reminiscent of the 1960s culture clashes. The final parallel is the profligate spending of the United States. On this matter, however, the potential consequences are far more severe in the 2020s. Whereas the 1960s marked the beginning of unsustainable spending, the 2020s will likely mark the curtailment of it.

Three Financial Currents Likely to Shape the Next Era

The Great Inflation offers a useful framework for evaluating the next several decades, but it is incomplete. Ultimately, it is impossible to identify all of the financial drivers of an emerging era in advance. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that the three issues that follow will play an important role. The first and most immediate issue is dealing with post-COVID-19 inflation. The second, and by far the most important, is dealing with the unsustainable spending of the federal government. The third, which is largely a product of the second, is the shifting philosophy in the U.S. regarding its relationship with the rest of the world.

Issue #1: Post-Pandemic Inflation

"There can be no danger of galloping or runaway inflation in the reckonable future unless our monetary and fiscal policies become utterly reckless."⁴

—ARTHUR BURNS, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (1957)

In 2021, post-COVID-19 inflationary pressures ignited in the United States. The causes were similar to the ones that fueled the post-World War I/Great Influenza inflation in 1919-1920. Nevertheless, Fed Chair Jerome Powell initially attributed post-COVID-19 inflation to "transitory" supply chain shocks and assured the American people that inflationary pressures would naturally dissipate. The dynamics of the 1919-1920 inflation suggested a different scenario was more likely. Throughout 1919, the Fed made the same miscalculation and waited a full year for inflationary pressures to subside. When it became apparent that tighter monetary policy was needed, the Fed abruptly raised rates by 125 basis points in January 1920, and another 100 basis points in June 1920. Inflationary pressures finally yielded, and the U.S. entered a sharp but brief recession in 1921.⁵

In 2021 and most of 2022, the Federal Reserve seemed largely, if not completely, oblivious to this precedent, which explains, in part, why they committed the very same error. The Fed claimed that post-COVID-19 inflation was a "transitory" event that was largely attributable to supply chain shocks. It was only after high inflation persisted for roughly 18 months that the Fed began raising rates aggressively, much like they did in 1920. Despite nearly everybody's expectations (including my own), the aggressive monetary policy tightening failed to return inflation to the long-term target of two percent, nor did it trigger a recession in 2023 or even 2024. This is because nearly everybody underestimated the staying power of the massive fiscal stimulus enacted during the pandemic. This included a particularly ill-advised third round of fiscal stimulus, which was absurdly dubbed the "Inflation Reduction Act."

Despite the Fed leadership's awareness of lingering inflationary pressures, they remained enamored by the prospect of orchestrating an unprecedented soft landing. By the summer of 2024, the Fed was anxious to return to a "neutral rate" of interest, and on August 22, 2024, Chair Jerome Powell announced an impending pivot toward more accommodative monetary policies. The subsequent reduction of interest rates by a total of 100 basis points during the last four months of 2024 defied one of the more important principles discovered during the Great Inflation, which is that ending extended periods of elevated inflation requires central bankers to decisively extinguish every last ember. Failure to do so allows inflationary pressures to reignite, which is precisely what appears to be happening now. Over the past five months, bond vigilantes have pushed up long-term rates; surveys of long-term inflation expectations have risen; and current inflation remains stuck around 3%.⁶

It is uncertain how the post-COVID-19 inflation will end—but it is clear that it is not over. Some planned policies of the Trump administration may be inflationary, while others may be disinflationary. The President has also voiced a dangerous and ill-advised intention to influence monetary policy by "lowering interest rates immediately."⁷ If the inflationary pressures turn out to be stronger than deflationary pressures, at a minimum, the Fed will need to leave rates higher for longer. It is also conceivable that they will need to raise them. This would test the commitment of the Fed to uphold their independence from political influence. It would also test the Trump administration's willingness to honor it. This could result in an epic battle between the Federal Reserve and the executive branch, which is a conflict that is not in the interest of the American people.

Issue #2: Unsustainable Fiscal Deficits

"The position of the United States after World War II was entirely abnormal and unsustainable. We came through unscathed. Our industrial power actually strengthened, while our potential competitors were substantially destroyed and needed our help to rebuild themselves…It has been both natural and desirable for others to catch up to us from a very depressed state."

—PAUL A. VOLCKER, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board

The nation's unsustainable fiscal deficits and unwieldy debt burden are likely to be the most powerful forces shaping U.S. economic and political events over the next several decades. This moment of reckoning was a long time coming. The spending binge began soon after World War II ended in 1945. As former Fed Chair Paul Volcker concisely explained in the above quote, the U.S. emerged as the world's wealthiest nation. Moreover, while the industrial infrastructures of nations across Europe and Asia lay in ruins, the U.S. "Arsenal of Democracy" fueled massive expansion of its industrial capacity and sharpened its technological edge. In the 1950s, the U.S. enjoyed an extraordinary period of economic prosperity. Jobs were plentiful, poverty rates fell dramatically, and the middle class thrived. The combination of exceptional wealth and a vastly superior means to produce it explains why many Americans are nostalgic about life in the 1950s.3

The image shows a tank assembly line at a retooled Chrysler facility that was part of the Arsenal of Democracy. (Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Unfortunately, the exceptional prosperity of the 1950s set the stage for the onset of chronic fiscal deficits in the 1960s. Politicians tolerated the deficits, in part, because debt-to-GDP levels had substantially declined as a result of exceptional economic growth and reasonably balanced budgets in the immediate post-World War II years. In Figure 2, the dip in debt-to-GDP levels in the 1960s and 1970s is clearly visible.

Figure 1: Total U.S. Public Debt as a Percentage of GDP (1792-2032E)

Source: Mark J. Higgins, Investing in U.S. Financial History: Understanding the Past to Forecast the Future, (Austin: Greenleaf Book Group, 2024).

The problem was that it was never realistic to expect the economic dominance of the 1950s to last forever. European and Asian countries steadily rebuilt their economies and the wealth and competitive positioning of the U.S. relative to the rest of the world weakened. Americans' perceptions of their relative position, however, failed to adjust at the same pace. Decade after decade, this emboldened politicians to continue expanding federal spending programs at an unaffordable rate.

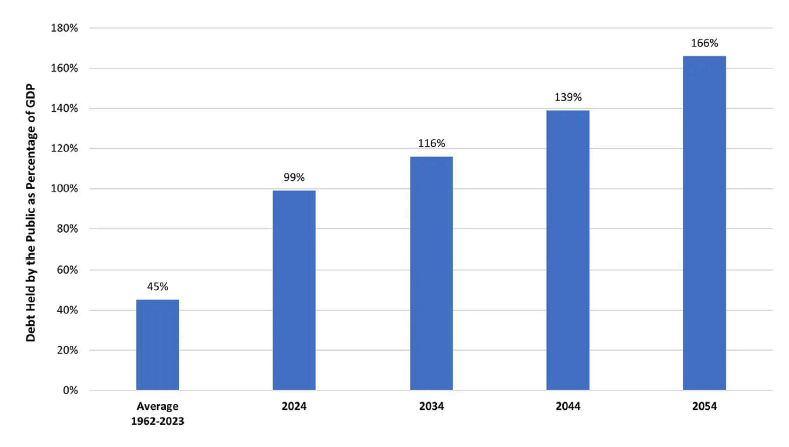

Few Americans have come to terms with the nation's distorted perceptions of its own wealth, but the ruthless laws of math do not lie. The data clearly reveals that the U.S. has spent far more than it can afford for more than half a century. As a result, the national debt has increased to dangerous levels, and is projected to increase much further at the present pace. This is precisely the situation that Alexander Hamilton sought to avoid when he advised Congress to establish a means for extinguishing the public debt during prosperous times. Figure 2 presents Congressional Budget Office data that shows past, current, and projected debt held by the public as a percent of GDP.

Figure 2: Past, Current, and Projected Total Debt Held by the Public to GDP (1962 - 2054)⁸

Many Americans cling to the fantasy that federal spending can continue at the present pace, but when pressed, they can rely only on magical thinking to justify their arguments. Some hope that the U.S. can outgrow its debt problems, much like it did in the late 1940s and 1950s. But those times were different. The industrial infrastructures of global competitors were in ruins, and several tailwinds (e.g., exceptionally high productivity growth and steady labor force expansion) are now headwinds. Others, such as proponents of Modern Monetary Theory, make the ludicrous claim that the U.S. can accrue debt forever because the nation possesses the world's dominant reserve currency. This argument may provide false comfort for a few years years (maybe even a decade or two), but empires eventually lose reserve currency privileges once the world no longer views their credit to be a risk worth taking. The Dutch suffered this fate in the late 1700s, and the British suffered it in the mid-1900s. The U.S. does not possess special immunity to this outcome.

It seems like the only realistic option is for the U.S. citizenry to acknowledge, confront, and overcome misperceptions about its own wealth. Accomplishing this feat may rank among the most difficult financial tests since the nation's founding. After all, the last time the solvency of the United States was called into serious question was in 1790. The next era of U.S. financial history will test the credit of the U.S., and it will be a completely unfamiliar experience for every American.

Issue #3: Trade and International Relations

"You should fully understand the special position that the United States now occupies in the world, geographically, financially, militarily, and scientifically, and the implications involved. The development of a sense of responsibility for world order and security, the development of a sense of overwhelming importance of the country's acts, and failures to act, in relation to world order and security—these, in my opinion, are great musts for your generation."⁹

—GENERAL GEORGE C. MARSHALL (February 22, 1947)

Blessed by enormous wealth after World War II, Americans abandoned their isolationist leanings for the first time in history. Few Americans realize that prior to that point, the default position of the United States was to remain largely detached from global affairs. After World War II, however, Americans willingly gazed far across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans searching for opportunities to rebuild a better world. This sentiment was expressed by General George C. Marshall in a speech he delivered at Princeton University.

On February 3, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the Economic Recovery Act of 1948, which allocated roughly $13 billion to European reconstruction. It is now known as the Marshall Plan in honor of its architect. In addition to providing desperately needed aid to Europe, the Marshall Plan created a strong bias toward engagement in U.S. foreign policy. This became an enduring precedent that persisted for nearly a century. It was an admirable precedent to be sure, but it was also one that was largely made possible by the extraordinary and historically anomalous wealth of the United States. All else being equal, it is much easier to be altruistic when you believe you possess a bottomless reservoir of financial assets to fund it.

President Harry S. Truman signing the Economic Recovery Act of 1948. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The United States Turns Toward Its Isolationist Roots

The world slowly but steadily changed over the last 80 years, and it has now reached an inflection point. In 2025, the wealth and competitive advantages of the U.S. remain strong in an absolute sense, but they have diminished in a relative sense. The U.S. is still the largest economy, but its share of global economic output has shrunk substantially since the 1950s. At the same time, chronic fiscal deficits have taken a toll on the nation's borrowing capacity.

The harsh reality for the rest of the world is that the U.S. is less willing to play the role it has played abroad since the end of World War II—and at a minimum, it is far less willing to fund it. U.S. debt capacity may not be exhausted from a technical perspective, but the coffers are nearly empty from a psychological perspective. As a result, the U.S. is now squarely focused on rebuilding its own wealth.

At the root of President Trump's tariff plans is pressure from the American electorate to rebuild the nation's wealth. To be clear, tariffs are not risk-less maneuvers. In a worst case scenario, they can trigger tit-for-tat retaliation, which causes all nations to suffer. Nevertheless, a large percentage of Americans appear willing to take that risk.

The most important point to absorb is that the U.S. is turning back toward its isolationist leanings, and it is unclear how long this shift will last and how far it will go. In the meantime, allies and trading partners would be wise to assume they are largely on their own until Americans once again feel comfortable with the adequacy of their financial reserves. Protective tariffs, freezing of foreign aid and withdrawal of military support are likely to be far more common in the foreseeable future.

Final Thoughts

"You will perceive Sir, I have neither flattered the state nor encouraged high expectations. I thought it my duty to exhibit things as they are not as they ought to be."10

—ALEXANDER HAMILTON, letter to Robert Morris (August 13, 1782)

In the summer of 1782, the American Revolution had taken a devastating toll on the colonists. The superintendent of finance, Robert Morris, dispatched many of his most trusted leaders to get a more detailed assessment of the economic conditions in the thirteen colonies. Alexander Hamilton was sent to the colony of New York where he observed catastrophic economic damage and widespread human suffering. He suspected that reports on other colonies were sugarcoated by his compatriots because they feared revealing just how bad the conditions were. Nevertheless, Hamilton refused to alter his report because he believed the leaders of the Revolution needed reliable information to make the best decisions possible.

This newsletter may seem heavy on despair and light on hope. My aim, however, is to channel the spirit of Alexander Hamilton and simply "exhibit things as they are" so that people can prepare and respond more effectively. None of the problems that this country faces are easily solved, but neither are they insurmountable. Admittedly, many of America's ancestors have experienced better times, but many have also experienced far worse. Fortunately, recognizing problems for what they are and designing innovative solutions is an enduring American tradition. It explains why the track record of this nation strongly suggests that Americans will overcome their present challenges, and the United States will continue the slow but steady mission of making this country and the world a better place.

Disclaimer: This is a personal newsletter. Any views or opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not represent those of any people or organizations that the writer may or may not be associated with in a professional capacity, unless specifically stated. This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, service, or considered to be tax advice. There are no guarantees investment strategies will be successful. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

1. Alexander Hamilton, Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit. January 9, 1790).https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-06-02-0076-0002-0001

2. Arthur F. Burns, "The Anguish of Central Banking," The Per Jacobsson Foundation, September 30, 1979,https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/FRB/pages/1985-1989/32252_1985-1989.pdf.

3. Janet Yellen's claim in a January 8, 2025 interview that fiscal stimulus during the COVID-19 pandemic added "a little bit" to inflation was an especially egregious example.

4. Arthur F. Burns, "Prosperity without Inflation." Millar Lectures, Fordham University. (1957).

5. Mark J. Higgins. "The Post-COVID Recovery is Unlikely to Resemble the Roaring 20s; The Years 1919 and 1999 Provide More Insightful Comparisons."Social Science Research Network. (August 23, 2021).

6. For more information on why financial history strongly suggested the Fed's pivot in August 2024 was an error, I encourage you to read the following newsletters posted on August 27, 2024, October 10, 2024, and December 20, 2024.

7. Paul Davidson, "Trump Says He'll Demand Lower Rates Immediately, Claims He Knows Rates Better than Fed." USA TODAY. (January 23, 2025)

8. Congressional Budget Office. https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#1.

9. George C. Marshall, "Speech at Princeton University." (February 22, 1947).

10. Alexander Hamilton. Letter to Robert Morris Dated August 14, 1782.https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0057-0001

This article is republished here with permission of Mark Higgins, Senior Vice President, and Author of Investing in U.S. Financial History. No further republication or redistribution is permitted without the consent of Mark Higgins. The views expressed herein belong soley to the author.

This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product or service. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Performance may contain both live and back-tested data. Data is provided for illustrative purposes only, it does not represent actual performance of any client portfolio or account and it should not be interpreted as an indication of such performance. IFA Index Portfolios are recommended based on time horizon and risk tolerance. For more information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc, please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit www.ifa.com. This is intended to be informational in nature and should not be construed as tax advice. IFA Taxes is a division of Index Fund Advisors, Inc.