There are many compelling reasons to use index funds rather than actively managed funds. For a start it's cheaper and, in the long run, that usually results in superior net returns. It's also simpler and easier, and involves less time and aggravation. But there is another big advantage of indexing that warrants more attention than it's given: with index funds you know exactly what you're buying, but with active funds you don't.

"When you buy a box of corn flakes," writes Mark Hebner, in his book Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors, "you expect to see corn flakes in your cereal bowl. You would not expect to see your bowl laden with granola or raisin bran with a few corn flakes mixed in. Consumers rightfully expect that packaging and labels accurately reflect the contents of their purchase. It just so happens, however, that the contents of actively managed funds often vary, sometimes significantly, from their labels or stated benchmarks."

Style drift is usually deliberate

What Mark is referring to here is a phenomenon known as style drift. Simply put, style drift is the divergence of a fund from its stated objective. This can occur if a particular security or asset class has a dramatic move that alters its relative portfolio weight. More commonly, though, it's the result of a deliberate decision by the fund manager to alter his or her investment style.

For example, you may have intentionally invested in a growth fund, but unbeknown to you, your active manager has invested 20 percent of the fund's assets in cash and bonds. Or you may buy a bond fund, only to discover, perhaps after a fall in the stock market, that the manager has moved 30 percent of the assets into equities.

In both of these examples, the manager's drift in style is a big deal. It fundamentally changes the composition of the funds you invested in. That, in turn, alters the risk exposure, expected return, and time horizon of your original investment. The underlying investments in the fund no longer match its name or style.

Why does style drift happen?

Why, then, is this allowed to happen? Well, the rules imposed by the regulator, the SEC, do permit a degree of style drift by active managers. The SEC recently updated those rules to ensure that mutual funds' portfolios match the strategies suggested by their names. But fund managers still have discretion and flexibility to diverge from their stated style, which they frequently do, particularly in times of market turmoil.

There are, however, other reasons why style drift is so prevalent. The financial industry, for example, has no commonly agreed standards for defining different asset classes or fund types. Firm A might choose to define U.S. small-cap stocks, for instance, in a very different way to Firm B.

Another issue is that asset management companies often craft their fund prospectuses very carefully, in order to give managers significant leeway to deviate from their fund's stated investment style.

How big a problem is it?

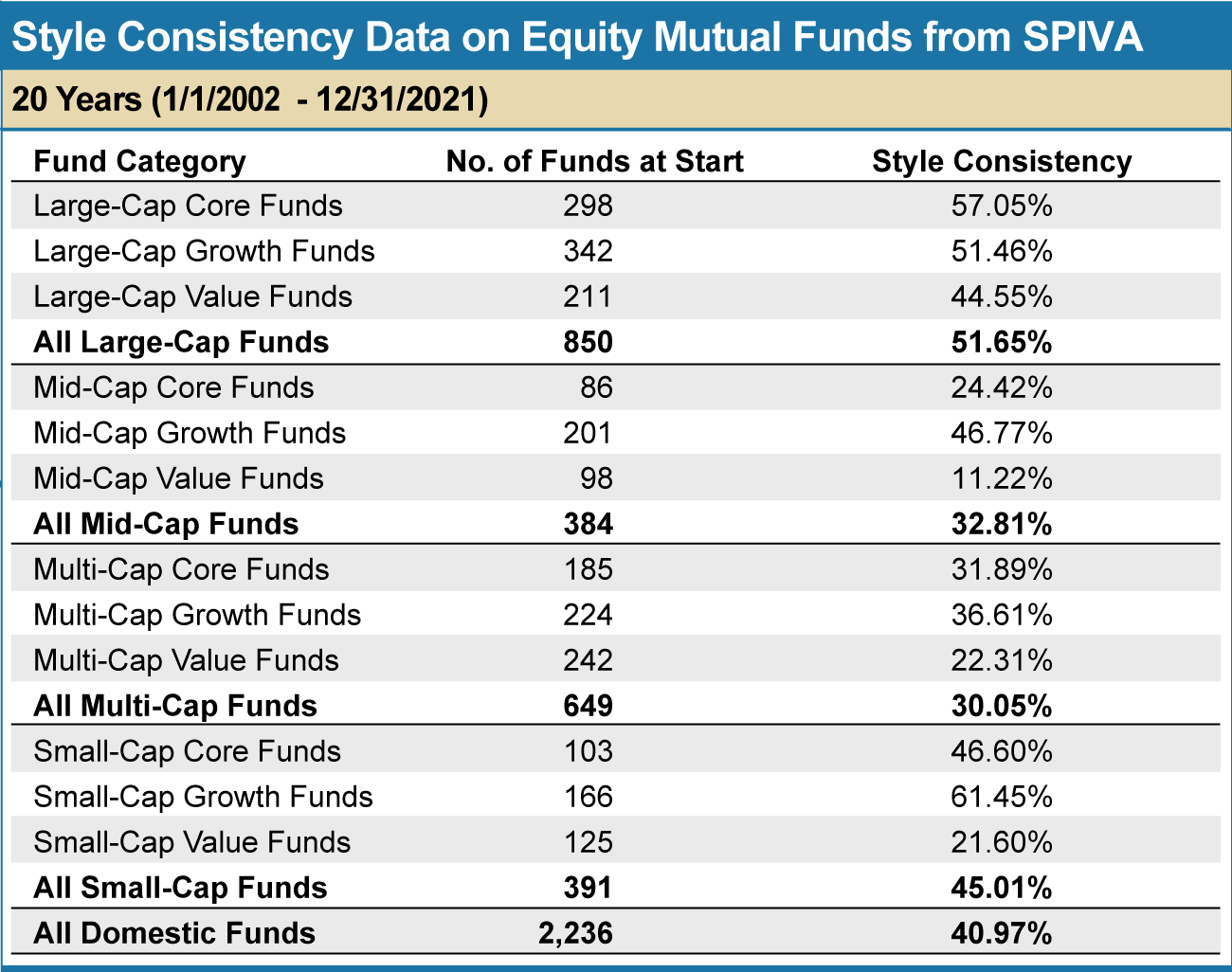

So how common is style drift? The answer is that it's far more widespread than most investors think. S&P Dow Jones Indices measures the style consistency of active funds as part of its ongoing SPIVA analysis. As you can see from the chart below, over the 20-year period from 2002 to 2021, only 40.97 percent of all U.S. equity funds maintained style consistency throughout.

Source: SPIVA® U.S. Scorecard, S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, eVestment Alliance. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indexes are not available for direct investment, and performance does not reflect expenses of an actual portfolio. Chart is provided for illustrative purposes. This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, or service or considered to be tax advice. There are no guarantees investment strategies will be successful. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

A classic example of style drift is Fidelity's Magellan fund in the 1980s. The fund's manager at that time, Peter Lynch, was lauded for consistently outperforming the S&P 500 Index. Yet a closer inspection of Lynch's record shows that his outperformance was largely down to a heavy concentration in small-cap stocks that weren't actually in the S&P 500.

Academics have demonstrated that, over long periods, small-cap stocks have generally outperformed large-caps, and this was certainly the case in the 1980s. So, in the case of the Magellan fund, it wasn't necessarily that Lynch was skillfully picking the right stocks; he simply chose to diverge from the fund's stated style and invest in a type of stock with a higher level of volatility and a higher expected return.

Sometimes style drift can have a far bigger impact on a fund's risk profile. An example of this is when bond fund managers invest in equities. Bonds — U.S. Treasurys in particular — are a relatively safe investment. They do sometimes fall in value, but they are much less volatile than stocks. Also, when stocks fall in value, bonds tend to rise, so the primary role of bonds in a portfolio is to dampen the risk of equities.

Bond fund managers are nevertheless incentivized to maximize returns. So, when bond yields are low, they typically try to improve returns by adding exposure to equities. For investors, though, there's a price to pay in the form of increased risk. Stocks are much riskier than bonds, and the high-dividend stocks that bond fund managers usually favor are particularly so.

Again, this practice of bond fund managers drifting into equities is surprisingly common. According to data from Morningstar, 468 mutual funds classified as bond funds held stocks at the end of 2021.

Tactical asset allocation

Of course, in theory at least, style drift can work in the investor's favor. By reducing exposure to an asset class that is about to fall in value and increasing exposure to one that's about to do well, a fund manager can potentially improve returns significantly.

Fund managers call this asset rotation or tactical asset allocation (TAA). Unfortunately, though, TAA is anything but straightforward in practice. It entails timing the markets correctly, which all the evidence shows is very hard to do. The vast majority of active managers do not have the skill to make the right calls with the required level of consistency.

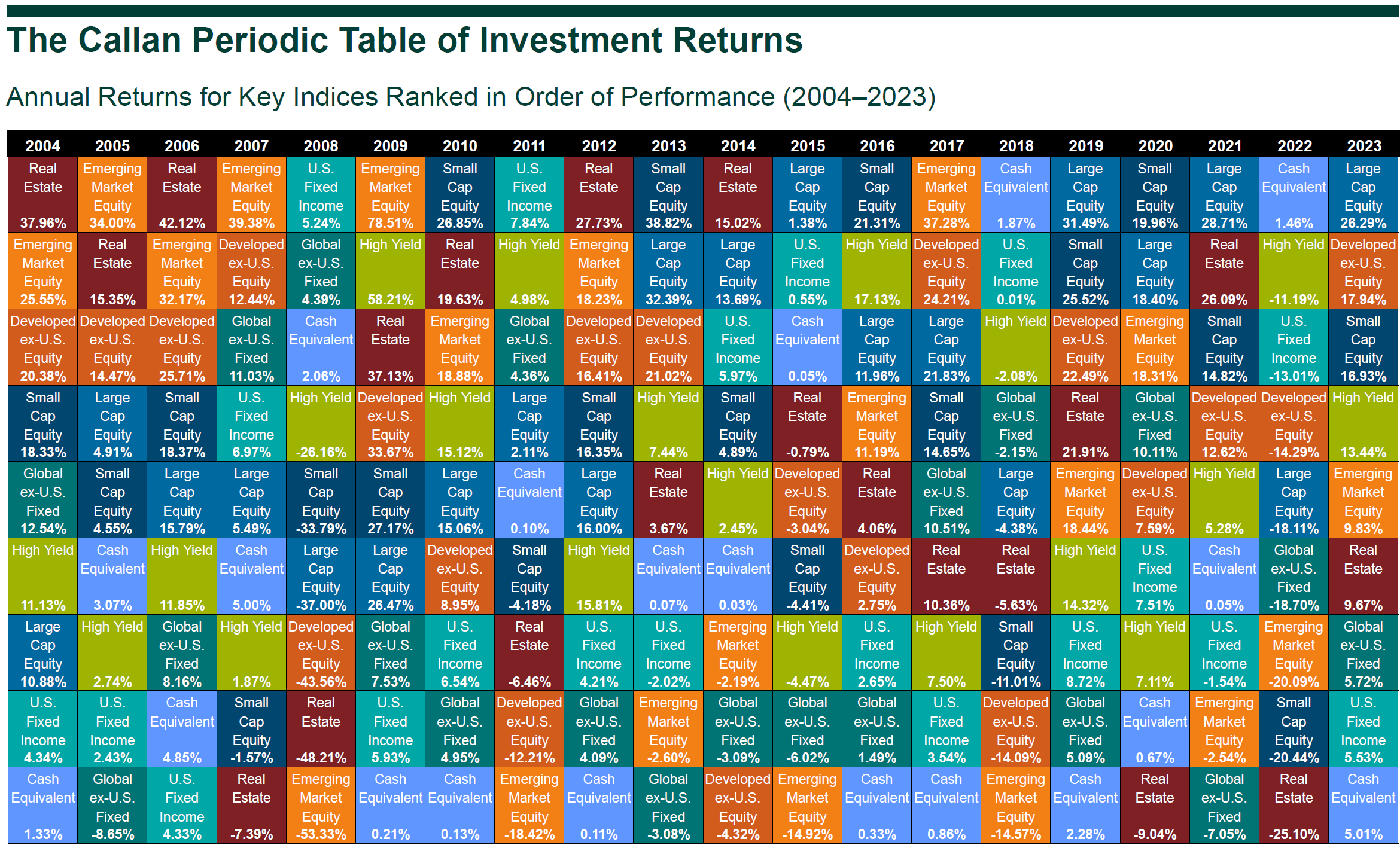

To understand why tactical asset allocation is so difficult, you only need to look at the chart below. It's called the Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns and it shows the annual returns for eight asset classes for each calendar year from 2004 through 2023, with the best performers at the top and the worst at the bottom.

The asset classes are color-coded, and, as you can see, high and low returns of key market indexes are completely random, following no discernible pattern.

Source: The Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns conveys the strong case for diversification across asset classes (stocks vs. bonds), capitalizations (large vs. small), and equity markets (U.S. vs. global ex-U.S.). The Table highlights the uncertainty inherent in all capital markets. Rankings change every year. Also noteworthy is the difference between absolute and relative performance, as returns for the top-performing asset class span a wide range over the past 20 years. The Callan Institute. © 2024 Callan LLC

Source: The Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns conveys the strong case for diversification across asset classes (stocks vs. bonds), capitalizations (large vs. small), and equity markets (U.S. vs. global ex-U.S.). The Table highlights the uncertainty inherent in all capital markets. Rankings change every year. Also noteworthy is the difference between absolute and relative performance, as returns for the top-performing asset class span a wide range over the past 20 years. The Callan Institute. © 2024 Callan LLC

Takeaways for investors

There are three main lessons that investors need to learn when it comes to style drift in active funds.

First, style drift can give a very misleading impression about how successful an active manager has been in the past. It's an example of what Craig Lazzara from S&P Dow Jones Indices calls "performance trickery." Research by Lazzara and his colleagues shows that bias plays a major role in explaining active manager outperformance across the capitalization spectrum.

"Whenever there are significant differences between the performance of capitalization-specific indices," says an S&P report from March 2021, "there are opportunities for managers to add value by moving up or down the cap scale. Such opportunistic moves may be commendable, but they are not evidence of skill at stock selection."

Secondly, if you use an active fund, you may well be taking more (or indeed less) risk than you think. Investment analyst Bob French put it this way: "You are giving control of your asset allocation to someone who has no clue who you are. They're focused on getting the best returns they can for their fund. They aren't focused on making sure their fund fits into your retirement plan."

Remember, for most people, getting the highest return possible is not the primary goal. Instead, they're looking to build a portfolio that will help them reach their investment objectives. Financial planners do this, says French, "by very tightly targeting the level of risk in your portfolio. And we can't accurately target the level of risk in your portfolio if the funds you use are bouncing all over the place."

The third and final lesson is that you don't need to worry about style drift at all. The simplest way to avoid it is to stop speculating and avoid actively managed funds altogether.

Instead, invest exclusively in index funds. That way you'll know exactly what you're buying — style-pure investments with the appropriate level of risk, and no surprises.

Robin Powell is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Quotes and images included are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as endorsements, recommendations, or guarantees of any particular financial product, service, or advisor. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.