A select group of market factors are known to drive stock and bond returns. Some offer fewer advantages to fund investors, such as momentum, which can prove difficult to capture without significantly running up trading and other transactional costs.

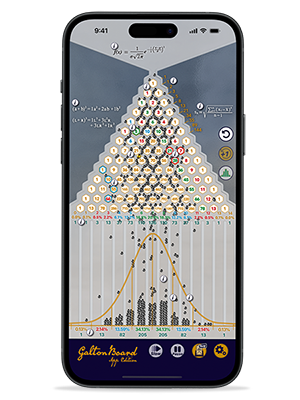

Research by professors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, however, has uncovered three "dimensions" of investment results that statistically explain more than 90% of stock returns over time. Better yet, IFA's wealth managers have been able to implement this trio of market factors in a cost-effective and efficient manner for their clients.

It's known in industry parlance as the Fama/French Three-Factor Model. These are identified as: The excess returns of a stock portfolio over a risk-free investment like a one-month Treasury bill (market factor); company size (market capitalization); and value (the book-to-market ratio, or BtM).

In addition, a company's profitability has been identified by Fama and French as a reliable dimension of stock returns to consider when putting together diversified global and passively managed portfolios for investors. (See the chart below.)

Market researchers in recent years have also been increasingly discussing negative correlations between higher levels of company investment activity and expected returns. In particular, such an analysis links how firms with higher costs of capital face more challenges in trying to increase corporate investments and grow assets.1

Notable work published in this area includes papers by: Fama and French;2 Michael J. Cooper, Huseyin Gulen and Michael J. Schill;3 and Efvgeny Lyandres Le Sun and Lu Zhang.4

Along these lines, one of the most consequential research pieces we've reviewed of the presence of a so-called investment premium was published in 2020 by a pair of analysts at Dimensional Fund Advisors. It has led DFA to include such a factor in the stock selection process in order to take advantage of this premium.

"In plain terms, what our research shows is a company that must invest heavily to sustain its profits should have lower cash flows to investors than a company with similar profits but lower investment. So, if both companies trade at the same price today, this implies that the company with higher investment and lower cash flows has a lower expected return," said Savina Rizova, Co-Chief Investment Officer and Global Head of Research at DFA.

Along with colleague Namiko Saito, she has co-authored the study, "Investment and Expected Stock Returns."5 In a related interview about such research, Rizova rather succinctly explained to us the link between a company's level of investment and expected returns to investors. As she put it:

"Valuation theory provides a framework for analyzing the drivers of expected returns. It says that a stock's price reflects expected future cash flows to shareholders discounted to the present through an expected rate of return. Valuation theory therefore predicts that for a given level of expected future cash flows, the lower the stock price, the higher the expected return on the stock. Similarly, for a given stock price, the higher the expected future cash flows to shareholders, the higher the expected rate of return. Expected future cash flows to shareholders are related to the expected future profits of the company. However, not all profits are returned to shareholders because companies may make investments. Therefore, expected investment lowers expected future cash flows to shareholders, holding expected future profits constant."

In order to quantify any investment premium for investors, Dimensional's research focuses on common methods used by companies to raise capital and grow assets. Those include equity and debt issuance. Rizova and her team also looked at a firm's retained earnings as a yardstick.

Taken on the whole, Rizova generically characterized a company's issuing new shares of stocks and bonds — along with its ability to retain earnings — as ways to generate "asset growth."

"This term (asset growth) is key to our research into observing and quantifying the investment premium," she said.

The major takeaway from Dimensional's research, Rizova added, is how its analysts and portfolio managers have decided to use such findings. While they've also observed a negative correlation between high investment and expected returns, she observed an "implementable" investment premium occurs much more prominently in small-cap stocks.

"It's true we see a negative relationship in both small- and large-cap stocks," Rizova said. "But we find more persistence in small cap stocks, providing greater opportunities to capture the high investment premium in smaller-sized stocks."

As a result, Dimensional is excluding stocks showing higher levels of investment across its global family of funds with exposure to small-cap stocks. This includes "SMID" (small-mid) and all-cap funds.

Taking into account an investment factor as part of a broader stock selection strategy that includes screening by other dimensions (market, size, value and profitability), can add 0.15% to 0.30% a year on average to a small-cap fund's return over time, Rizova tells us.