Undergoing Maintenance

This article is currently undergoing maintenance and is unavailable at this time. Please check back later. Sorry for the inconvenience.

About Index Fund Advisors

Index Fund Advisors, Inc. (IFA) is a fee-only advisory and wealth management firm that provides risk-appropriate, returns-optimized, globally-diversified and tax-managed investment strategies with a fiduciary standard of care.

Founded in 1999, IFA is a Registered Investment Adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that provides investment advice to individuals, trusts, corporations, non-profits, and public and private institutions. Based in Irvine, California, IFA manages individual and institutional accounts, including IRA, 401(k), 403(b), profit sharing, pensions, endowments and all other investment accounts. IFA also facilitates IRA rollovers from 401(k)s and 403(b)s.

Learn more about the value of IFA, or Become a Client. To determine your risk capacity, take the Risk Capacity Survey.

SEC registration does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission nor does it indicate that the adviser has attained a particular level of skill or ability.

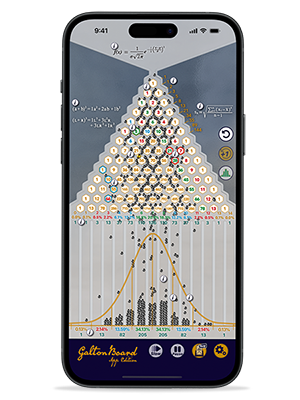

IFA's

— Risk Capacity —

Survey

Please estimate when you will need to withdraw 20% of your current portfolio value, such as a need for a house down payment or some other major financial need.

- Less than 2 years

- From 2 to 5 years

- From 5 to 10 years

- From 15 to 20 years

- More than 15 years

Find a portfolio that matches your Risk Capacity