The human brain is a truly wondrous thing. Though weighing only around three pounds, it contains approximately 86 billion neurons and is capable of processing around a billion billion (that's 1,000,000,000,000,000,000) calculations every second. And yet, strangely enough, there is a simple concept that even this extraordinary organ struggles to understand — randomness.

Why is that? Well, human beings have evolved to dislike uncertainty. We crave predictability. We want to understand the complex world we live in and to feel a sense of control over our own destiny. So we see patterns where none exist; we mistakenly read meaning into entirely random data.

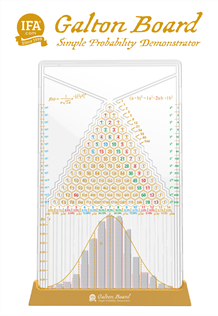

Say, for example, you watch someone flipping a coin. If the coin lands heads up several times in a row, you might think that tails is "due" to come up next. You might, conversely, assume that, because it's gone on so long, the run of heads is likely to continue. Either way, your thinking would be flawed, because the probability remains exactly 50:50.

Markets are far more complex than we realize

We make the same mistakes when thinking about the stock market. We like to think we understand the market. Even those who accept they don't understand it nevertheless assume there are very clever people who do and can be trusted with managing their investments.

But the stock market is an immensely complex ecosystem, driven by a multitude of factors including economic indicators, company performance, political events and investor psychology. In fact, it was shown as long ago as 1900 by a French mathematician named Louis Bachelier that, at least in the short term, stock prices move in an entirely random fashion.

One of several prominent academics to have been inspired by Bachelier is the Princeton economics professor Burton Malkiel, author of the best-selling book A Random Walk Down Wall Street. In the book, Malkiel describes how he once had his students create charts of fictional stocks by flipping a coin. The stocks started at a price of $50. Each day, depending on a coin flip, the stocks either gained or lost fifty cents in value each day. The students soon realized that each stock's "investment history" looked entirely realistic.

"One of the charts showed a beautiful upward breakout from an inverted head and shoulders (a very bullish formation)," wrote Malkiel. "I showed it to a (professional) who practically jumped out of his skin. ‘What is this company?' he exclaimed. ‘We've got to buy immediately. This pattern's a classic. There's no question the stock will be up 15 points next week.'"

Are you guilty of gambler's fallacy?

That pro investor fell for what behavioural scientists call gambler's fallacy. This is a well-documented cognitive bias where an individual believes, incorrectly, that the occurrence of a random event is less likely or more likely, depending on the outcome of previous events.

The truth, of course, is that every coin flip is independent of the previous one. Similarly, because daily stock market movements are essentially random, the fact that the market, or the price of a particular stock, rises or falls on one day tells us nothing about what it will do the day after.

Despite this fact there is constant speculation in the media about "what to expect" on the markets every day. As Nassim Taleb wrote in his classic book Fooled by Randomness: "Just as one day some primitive tribesman scratched his nose, saw rain falling, and developed an elaborate method of scratching his nose to bring on the much-needed rain, we link economic prosperity to some rate cut by the Federal Reserve Board or the success of a company [or country] with the appointment of the new president ‘at the helm.'"

Takeaways for investors

Given that market movements are so unpredictable, what, then, is the best way to invest?

Well, the first thing is to stop speculating. You might make the occasional correct call, but nobody buys and sells just the right stocks at just the right time with any degree of consistency.

The reason is simple. As IFA founder Mark Hebner explains in his book, Index Funds: The 12-Step Program for Active investors, current prices reflect all known information. "At all times," writes Hebner, "we only know the current and past price of any security. Where the price will be even a second later is unknowable. The market continuously sets prices in response to news, which, by its nature, is unpredictable."

So, rather than chasing returns by constantly seeking to adjust your portfolio, simply accept the fact that, in the short term, prices move in a totally random fashion.

Switch your focus instead to the very long term. Over much longer periods, market movements are more predictable. True, they can be very volatile, and bear markets can last a long time, but history shows that disciplined, diversified investors have almost always been rewarded for their patience.

By doing less, and paying less in fees and charges, investors maximize their chances of achieving their financial goals.

One last thing: ignore any news story that implies a trend in stock prices. Headlines often suggest that the market is "going up or going down". As Hebner points out in his book, it's far more accurate to say "the market has gone up or has gone down."

I even saw a headline recently that blared "S&P 500 Rally Flashes Signs of Fatigue Near Record". As one commentator rightly pointed out: "The S&P 500 is not a person. It doesn't get ‘fatigued. If it did, it wouldn't ‘flash' any signal."

Remember: humans have memories, but markets definitely don't.

Robin Powell is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Quotes and images included are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as endorsements, recommendations, or guarantees of any particular financial product, service, or advisor. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.