Two significant consumer trends have coincided in recent years. One is the growth in gambling, such as buying lottery tickets, sports betting and going to casinos. The American Gaming Association reported record-breaking revenues for the gambling industry in 2021, with revenue surpassing $53 billion. The second trend is the rising number of people trading individual stocks. Brokerage firms like Robinhood, Charles Schwab, E*TRADE and TD Ameritrade have reported substantial growth in the number of new retail trading accounts and in trading volumes.

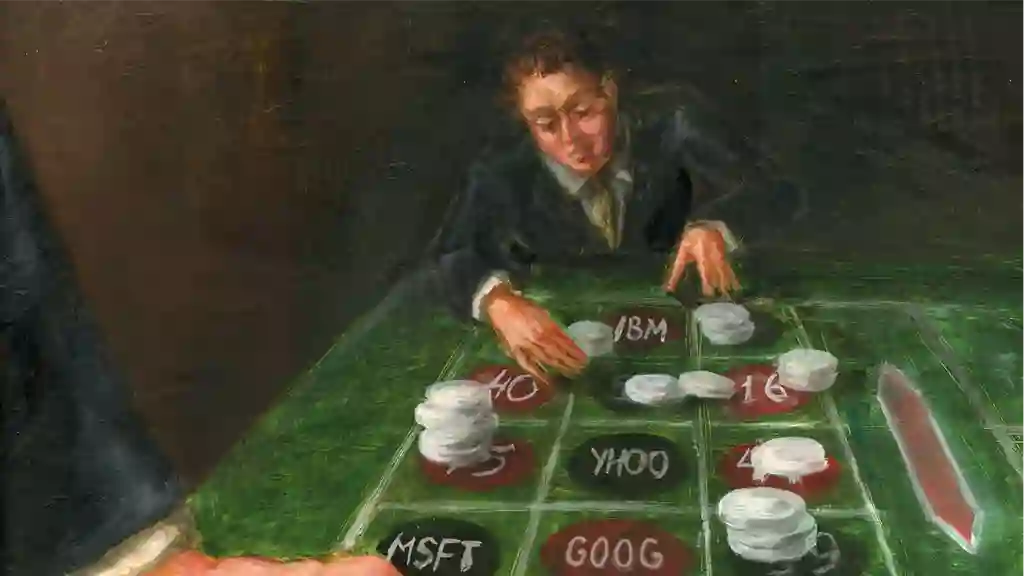

So are these two trends in any way related? You might think there's a distinction between betting, say, on a horse race, or playing online roulette, on the one hand, and buying the stock of a listed company on the other. The first two, most would agree, are gambling activities. But buying, say, a stock like Apple or Amazon seems more like a sensible investment.

Brokerage firms are certainly keen to reinforce this perceived distinction. Robinhood's marketing slogans, such as "Investing for Everyone" and "We are all investors," certainly give the impression that it sees itself as a service not for gamblers but investors. TD Ameritrade's slogan "Where smart investors get smarter" goes further, suggesting that trading stocks is for sophisticated investors who really know what they're doing.

But is there really such a big difference between gambling and stock trading? The overwhelming evidence is that there isn't.

A Question of Risk

Let's go back to basics. All investing involves risk. There are two different types of risk — systematic and non-systematic. Market risk is an example of systematic risk, as is the risk of owning small-cap or value stocks. Systematic risk cannot be diversified away: there's nothing we can do about it. On the plus side, systematic risks are compensated. That is, we expect a positive outcome for taking them.

Non-systematic risk is the risk of an individual stock, or indeed bond. Because non-systematic risks can be easily diversified away, using index funds, they are not compensated. In other words, you should not expect a long-term positive outcome for betting on a single company. Holding a large position in an individual stock is therefore irrational.

Markets are Efficient

Another crucial concept to understand is market efficiency. All available information is already reflected in market prices. Prices move up and down in response to new information, which is, by definition, unknowable — unless that is, you're an inside trader, in which case you're breaking the law.

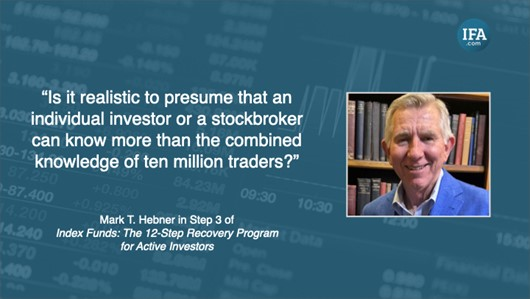

"No one can predict with certainty the direction of a stock," Mark Hebner explains in Step 3 of his book Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors. "Think about it from a purely logical perspective: Is it realistic to presume that an individual investor or a stockbroker can know more than the combined knowledge of ten million traders?"

Of course, you could argue that markets are not perfectly efficient, and that there are examples of stocks that are either overpriced or underpriced. That may well be true, but it's not the point. Because prices reflect all known information, identifying mispriced securities in advance is impossible to do on a consistent basis.

Individual Stock Performance is Erratic

If you're not convinced that stock picking is extremely difficult, take a look at the chart below. It shows the performance of 16 stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average from the start of 2004 to the end of 2023. The stocks with the highest returns are at the top of the chart and the stocks with the lowest returns at the bottom. You'll see that performance is very inconsistent. Stocks are rarely around the top, or the bottom, of the chart for very long, and one year of high returns is often followed by a year of low returns, and vice versa. Trying to identify, in real time, which of these stocks were going to perform best — and worst — in any one year would have been virtually impossible.

Why Not Buy the Best Companies?

"OK," you might be wondering, "performance is very erratic from year to year, but what if I buy a selection of the best stocks and hold them for the long term?" Well, investing for the long term is definitely the way to go. Most traders do far too much trading, and the more they trade, the greater the costs they incur, and the more mistakes they make. But buying individual stocks with a view to holding them for a long time is still not advisable.

So why is that? Well, one reason is that there's no such thing as a "good" stock to buy. Yes, there are plenty of examples of good companies, but they're already priced accordingly, and the higher the price you pay, the lower your expected return will be.

Another reason why buying and holding the most successful companies is a bad idea is that there is no guarantee that they're going to sustain that level of success in future. Past performance tells us nothing about future performance. In fact, it's very common for a company to achieve many years of growth and then, for whatever reason, struggle to maintain it.

The next chart shows the performance of companies before and after joining the ten largest U.S. stocks between 1927 and 2022. In the three years before joining the top ten, the average outperformance of these stocks was 27%; that fell to just 0.6% in the three years after joining. In the ten-year period after joining the top ten, those stocks underperformed the broader market by an average of 1.5%.

What About Buying Unloved Stocks?

What if, armed with that evidence, you decide that, instead of buying into companies that have already achieved success, you're going to look for unloved stocks whose current prices don't reflect their true value?

Well, there is some logic to that approach. Over the long term, financial academics have found, value stocks have outperformed so-called growth stocks, or well-established stocks. The big problem with that strategy, though, is what statisticians call skewness. Simply put, there are far more losers than winners. A 2017 study by Hendrik Bessembinder showed that market returns were driven by only around 4% of stocks. The remaining 96% of stocks didn't even outperform U.S. Treasurys.

That's an extraordinary statistic. Just think about it: you would have been better off taking no risk at all than holding 96% of individual stocks in the US since 1926.

Another study that shows how widespread underperformance is, was published in 2014 by J.P.Morgan. The researchers analyzed the returns of 13,000 stocks that were included in the Russell 3000 index between 1980 and 2014. They found that 40% of them suffered a decline of 70% or more from their peak value, without a significant recovery. Of those stocks that suffered severe declines, 67% underperformed the index over the period, and 40% had negative returns. What's more, the study found, these huge declines in value didn't just happen in recessions or market downturns — they happened all the time.

Even Most Professionals Fail

In case you need any more evidence that trying to buy and sell the right stocks at the right time is a fool's errand, you only have to look at the track record of professional stock pickers.

Active fund managers have a huge advantage over ordinary investors. They have large research teams at their disposal and easy access to the very latest information. They also visit companies in person and grill their board members to help them gauge just how good (or otherwise) those companies' prospects are. Yet, despite those advantages, the vast majority of active managers fail to outperform the market on a long-term and properly cost- and risk-adjusted basis.

Even in cases where a fund manager has outperformed, it can be very hard to tell whether they did so through skill or luck. The chart below shows that, between 2002 and 2021, hardly any fund managers delivered statically significant alpha, or outperformance.

Remember, fund managers aren't stupid — they're mostly highly intelligent individuals. If there are barely any fund managers with the skill to produce positive long-term outcomes through stock selection, do you honestly think that you can do any better?

The Odds are Stacked Against You

In summary, successful stock picking is far, far harder than most people imagine, and the odds of success are heavily stacked against you. It's virtually impossible to identify, in advance, the stocks that will have the highest returns in the future.

Of course, it's perfectly true that people have made big profits buying individual stocks. You may well know of some yourself. But the tendency in those situations is to attribute that success to skill when, almost certainly, it was nothing more than luck.

Don't forget either that buying individual stocks can be very risky. Enron, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns are examples of once highly prized stocks whose value fell to zero, and there are bound to be more in the future.

In the words of Mark Hebner, "picking stocks is an ill-fated strategy that wastes time, energy, and money." Don't do it.

Robin Powell is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Quotes and images included are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as endorsements, recommendations, or guarantees of any particular financial product, service, or advisor. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.